|

Streets of London [3MB]

Streets of London [2MB]

|

RALPH, ALBERT & SYDNEY

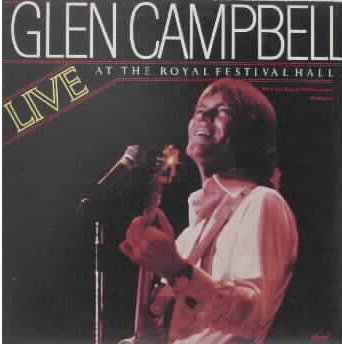

GLEN CAMPBELL

Harry

Chapin: an

eye for losers

Author: Derek Jewell

Publication: Sunday Times

Date: April 10th 1977

It

is scarcely possible to rank Harry Chapin among contemporary singer-

songwriters, for he stands virtually alone. It is also hard to believe it

has taken so long for so sparklingly original a talent to play a solo

concert in London.

He

managed it triumphantly after thirty-four years and six superb albums at

the New Victoria last Thursday.

The hall was not quite full, which will not happen again. No one who was

there can fail to persuade six other people along next time.

Chapin's

gifts are liberally in evidence on his albums, of which the last three

(all Elektra) reveal the most: Verities and Balderdash, Portrait

Gallery and On The Road To Kingdom Come. They show how his

inspiration springs from the daily encounters of American living, yet also

how the situations he depicts are often allegories for the universal

modern condition. 'Cat's In The Cradle', about a father-son relationship,

is typical Chapin. The son worships the father, wants to grow up like him.

The father is too engrossed in business. 'There were planes to catch and

bills to pay, he learned to walk while I was away.' Suddenly the boy is

grown, married; the father is alone. Now the son is too busy to

visit. 'He'd grown up just like me, as the painful punchline observes.

As

dramatic narrative alone, that song is compelling. Similarly, Chapin

observes a meeting between an old man and a waitress in a cafe, a chance

encounter of old flames in a taxi; a crucifixion by metropolitan critics

of a singer from the sticks who never opens his mouth in public again.

'Music was his life,' sings Chapin. 'It was not his livelihood.'

Chapin

has an unerring and pitying eye for life's losers; not heavily tragic

losers, but those for whom the pieces never quite fall together.

Simultaneously, he celebrates the strength of the human spirit which

survives loneliness, discovers the comic moments of episodes with which

his listeners can continually identify. In that coincidence lies the

secret of the best popular songs.

Chapin

sings in a clear, pleasant voice, using unfussy melodies and arrangements

played by a small backing group within which a cello provides haunting

counterpoints. His stage personality is captivating. He did as he wished

with Thursday's audience. As he hunched dumpily in his chair, tousling his

hair, talking wittily and relevantly about the circumstances of his songs,

himself, and his musicians, not a soul stirred, except to laugh or

applaud. The final standing ovation was spring-heeled and genuine. London

will see no more absorbing concert this year.

Earlier

last week, at the Albert Hall, Glen Campbell and Jimmy Webb had a larger

audience, without stirring them so deeply. Campbell is excellent at what

he does, in intonation and style as true to his Western roots (born in

Delight, Arkansas, once a cotton-picker) as Chapin is to his Greenwich

Village background. Yet where Chapin gets inside every song he sings,

Campbell seems too often a spectator, smoothing out tunes and meanings

alike. Few shocks, few insights - just a pleasant flowing countryish

sound.

He

can, it seems, do anyone's music. Still slim and lithe, he was once a

Beach Boy (I965), and revived their hits fluently. He imitated

Elvis. He rocketed through the William Tell Overture on

guitar with the finesse of a computer print-out.

He

has the great good fortune often to sing Webb's fine songs - 'Wichita

Lineman', 'Galveston', Macarthur Park' - and here performed several. Webb

himself sang 'Didn't We' which, like the others, is already a modern

classic. But the gloss of Campbell's breezy performance will not endure

like the grittier I50 minutes of Harry Chapin's.

back

to top

|