|

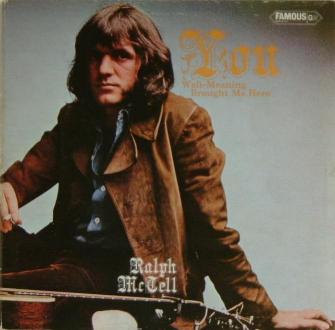

CONCERT PROGRAMMES Ralph McTell Timeline, 1973 Ralph McTell Interview, 1974 Conversation Extracts - 1989 In Conversation with Billy Connolly - 1989 1992 Interview [part one] 1992 Interview [part two] Black & White Tour Programe 1- Interview - 1994 Black & White Tour Programe 2 - Wizz Jones - 1994 Black & White Tour Programe 3 - John B. Jones - 1994 Sand in Your Shoes Interview _______________ |

RALPH, ALBERT & SYDNEY Concert

Programme

Concert

Programme INTERVIEWER:

O.K. Ralph the record, that's what's been taking up most of your time recently. RALPH:

That's right, so where do you want to start? INT:

Well what about the title, you said you were going to call it Easy? RAL:

That’s right we're calling it Easy. INT:

O.K. . . . Why? RAL:

. . . Well originally we were going to call it Take it Easy but Take It which is

a quote from Woody Guthrie (my all time fave rave) but that could sound a little

pushy ... it' it was taken the wrong way, so I just took the middle word 'Easy'

because the word appears in a couple of the titles on the album and . . . the

general feel of the album is Easy . . . the sleeve design is Easy. In fact the

only tiling that wasn't Easy was the Recording. INT:

You've beaten me to the obvious follow-on. Was it an easy album to put together? RAL:

Yes and no. In some ways it was the easiest record I've ever made but in other

... well at times it seemed as though I was never going to get the time to

finish it. Your see the sessions were spread over a long period of time ... I

had tours interrupting it and there was a lot of changing around and messing about so it seemed to take a lot

longer than it needed. The only pressure towards the end was the pressure of

time and that wasn't really pressure because in a way it helped get the pace in. INT:

When you say that it was recorded over a long period does that mean that the

songs are ones that we know already? RAL:

Oh no. It was just that the sessions started about August and went through right

up until Christmas. In fact the titles that we finally put on were just about

all recorded after I finished my University tour in September or whenever it

was. Although I wrote "Run Johnny Run" quite a while ago . . . when I

was on tour with the Natural Acoustic Band in fact. And there's another one I've

forgotten the title . . . "Let Me Down Easy". I wrote the tune to that

almost three years ago but never wrote any lyrics. INT:

Well how many titles did you record? RAL:

We must have put down about fifteen tracks . . . fourteen or fifteen, but in the

end we only used about ten. INT:

How did you decide which ones to include. RAL:

In a way they chose themselves by the end of the sessions the tracks seemed to

have developed a feel as they were getting done so ... those were the ones that

got used. INT:

What about the ones that got left off? RAL:

I dunno I still like some of the songs, maybe I'll use them on the next one. INT:

You spoke a moment ago about pressure then discounted it. Do you enjoy

recording? RAL:

I enjoyed it this time. But it always feel a bit of pressure because you've got

to be better than the last line. Errr ... I can get very mike shy in a studio

... I don't worry about microphones live but I worry about them in the studio or

at least I used to because there is just a string of people behind the glass and

no audience. INT:

I suppose that working so much in front of huge audiences you must find

recording a bit solitary. RAL:

I could easily be ... that's why I always try to work with people like Tony

Viscont and Danny Thompson because I know them as friends as well as

professionals . . . and that's why I was so pleased to be able to record most of

the Album at John Kongos' studio because it is a great studio and we knew each

other even before the studio was built. INT;

Well you sound pretty happy on the Albums. There's one track in particular at

the end of side one . . . RAL:

"Stuff No More Right? You see that was almost the last title that we did

and we were feeling good about the way it was all going . . . and we had a

little wine to drink and an old mate called Ivor (who is included in the song)

came down with a great deal more and ... we enjoyed that as well and the lyric

seemed to work out quite well too ... it also features the amazing Mr Thompson

on Hi Hat and Bass Drum ... in fact you can hear him complaining about the extra

work over the intro'. I'm glad it worked out. INT:

Maginot Waltz is on the Album and is also a song that I've heard you play live. RAL:

I wrote Maginot a couple of years ago and I was going to include it on the last

record but it didn't seem right but it's definitely right for this one.

Incidentally, that is the only track off the album where I didn't use a thumb

pick . . . that one's a finger nail job. INT:

It was also a track that you did virtually alone . . . almost identical to the

way we would hear it on stage . . . except for the Harmonium. Do you think of

yourself as a keyboard player. RAL:

Oh yes I think I'm really fantastic as a keyboard player . . . mostly sleeping

on it. I can't play the piano and never profess to be a keyboard man. INT:

So you can sleep on the piano as well as the next man. RAL:

Yes, that and spill drinks all over it. INT:

What about some of the tracks where you were joined by other people like

"Run Johnny Run"? RAL:

O.K. What about it? INT:

. . . Well it seems a lot fuller sound that you get on stage. RAL:

Well, obviously I can't do it like that on stage unless I have about four other

people with me ... but if the song is right it is worth doing something with it

in the studio . . . John Kongos came out and did some high backing vocals and I

had Lyndsay Scott on fiddle who used to be with the JSD Band and now has his own

band called Baby Whale. Danny Thompson and Gerry Conway and Mr Unique - Bert

Jansch - he's coming out of the right hand speaker. You see I played on Bert's

last album. I don't think I would have had the courage to ask him to play on

mine unless I had. INT:

I'll remember to listen out for the right hand speaker. What about "Take It

Easy" because that actually has the line in it 'Take it easy but take

it?" RAL:

That's my personal dedication to Guthrie. I wrote the song to sort of say . . .

it's partly autobiographical about my first long stay in Paris . . . except I

had a bit more luck than the geezer in the song. INT:

I see that you have Michael Bennet on backing vocals. Is that the same guy as

"Whisphering Mick" from your early Albums? RAL:

Right... we used to call him Whispering Mick because he had such a loud voice

and an even louder laugh. In fact Wizz gave him that name and he's on that track

too. Mick used to play in our jug band. I think he was probably the worst

washboard player in the world but one of the best singers that 1 know, although

he never works. He was staying around my place at the time - he seems to spend

his entire life between staying with me and living on his own in someone else's

ruined manor house somewhere in deepest Cornwall. Anyway he was there at the

time we collared him into the studio and do his bit ... I was really surprised

how nervous he got it was really out of character - still he got it down really

well in fact I want to include some of his poems in the programme. INT:

Well you say that about Mick but I'm sure that a lot of people might think that

the song itself is a little out of character with what they have come to expect

from you. I mean ... I think that people may have come to expect a more retiring

sort of person from your previous albums. RAL:

Sure. But you've got to remember that a lot of my albums that are still getting

played were recorded years ago . . . and maybe that's how I felt then. No the

song's not out of character with the way I feel now. Look I'm sure that there

are some people who think of me as gentle and all that but if we get cup up in

the traffic I'm more likely than my roadie to jump out and start getting angry -

and if I'm behind the wheel I can shout and swear as loud as the next man. In

fact, I have even been known to stamp my foot when I get my paddy up - oh I

don't know, 1 suppose it depends where you are and what you're doing. INT:

Can I ask you about the song "Let Me Down Easy". Is it

autobiographical or more general? RAL:

I think that most people have been through the situation in the song . . . and

if they haven't then they are a little unfortunate . . . although it might be a

bit sad to experience you can get a lot more out of it. So often the boot seems

to be only on one foot. Most of my friends have been in love with someone who

was falling out of love with them . . . and known what it was leading to.

AL

STEWART Eventually

we didn't know what to do it was like the English cricket team, bang, bang,

bang, they were all going out. We sent Hope Howard out and he comes on

and he starts singing the Banana Boat Song or whatever and they go absolutely

mad and for the next four hours Hope Howard played and got I think about a

hundred and sixteen encores, and the rest of us were sitting in the dressing

room, going what is going on here. If I had put that bill back together today,

you know Bert, John, String Band, Ralph, Roy, Me, it would be worth something,

you know, it would probably fill up, a fair sized folk club! In those days, I

mean that's my first memory, they really didn't want to know... ...

There was a little bit of rivalry. Basically, after the dust had settled it

turned out that there was Harper, McTell and myself who if there was any

rivalry, we all did the College circuit so consequently we would be very keen to

find out what the other one was making or who was getting the most gigs. So I'd

play Warwick University and get 500 people and I'd say, you know, who was here

last week? Ralph. How many people turned up? Oh, 1,000. I'd go oh God. I'd sort

of be worried about Harper, you know - 300, oh, I'd feel pretty good. And, I

don't know why because I mean all this time has gone by and you know it's

totally meaningless now. I think when you're a kid you're looking for some sort

of acceptance. That's the only thing I can think of. Interestingly enough I

mean, in the case of both Ralph and myself somewhere along the line we had a hit

and I think that that was it. In fact I remember actually, Ralph did a thing in

the Melody Maker where he said "I don't give a monkeys about success".

Do you remember that article? And I picked that up and I thought well that's not

quite the way I remember it from the days of the Cousins. But I think once

you've had a little bit of success you can say that, you know.

...

We were the sort of new boys, I mean Bert and John were like established stars

and then there

were people way behind us like Davy Graham and you know sort of the old timers

you know who when we first started, like people like Red Sullivan and Martin

Windsor had been already around for about 20 years and so I think we were pretty

much aware of being sort of young upstarts in a way or at least I was I don't

really know how Ralph felt about it all... ... The real folk singers were the

ones who had their hands over their ears and they would go... 53 verses about

the silkies off the North of England... oh you know, Scotland or whatever. And

that was one thing but Ralph and I were really sort of pop folk, I don't know

how else to put it and I came with Dylan, the Birds, Paul Simon and that kind of

thing as my influence. Ralph,

a little bit more because Hesitation Rag was about the first thing I ever heard

him play so he obviously had the blues influence and the ragtime influence, but

it was still the thing once you got into writing your own songs it becomes

almost pop folk... it was very difficult because the pop scene at the time was

like the Walker Brothers, I don't know whether you remember this and they

absolutely didn't want to know about people with acoustic guitars, and the folk

scene was people with hands over their ears... Then

we all went to play Concerts. I was very surprised, I mean it was one of those

nice things that happened you know, I mean a lot of people fell by the wayside

if you want to go back and look at the bills, I have seen some early bills from

those days, some people made it and some people went off and sold used Fords,

you know, it's just one of those things. So,

you go where the work is. I didn't have the folk luggage to carry around... but

I think that you can commute round and play any country in the world, and its

sort of evened out, everything's gone back to being pop folk again... ...

The interesting thing was just sitting in there with Ralph and Roy and myself

just like playing the guitars and it seemed almost like it could have been 20

years ago. I mean the amount of time that goes by nothing really significant

changes. We could all be back in the Cousins and I might have sort of a quick

flash about you know was there

really 20 years that went by and you'd probably would say no. We don't change, I

don't feel any different, Ralph probably doesn't feel any different. I think

nothing really significant changes about you,

you play the music which you play and you stick with it. What changes is

public perception of you and that's unimportant ultimately because you just, do

this above all selves you know to thine own self be true. MARTIN

CARTHY ..

.He doesn't do folk clubs anymore you know that. But he's probably one of the

most underrated songwriters around, people don't give him credit for the breadth

of subjects, the range of subjects that he chooses to cover. They imagine him as

just a bloke who writes a couple of songs and plays a bit of ragtime but there's

a bit more to him than that... I think his influence has been more one of

attitude, people admire him because he's stuck to his guns. He had a lot of

pressure on him at one time and he's stuck to his guns and he's gone his own way

he's never allowed anybody to influence him but him. He's got a lot more bite in

what he writes than people give him credit for, his songs when he wants to he

can actually bite quite deep and I'm an admirer... ROY

HARPER

Concert

Programme BILLY...

everytime I come to your house I learn something. I came and I got the James

Burke three finger picking book and I went away and learned it, and the last

time I was here I got that Clive Palmer album and I was determined to learn that

tune BANJO LAND and so I'm hoping today if you've got something you can ...

maybe show me something. I came to Cambridge last night hoping you could show me

something but I ran away before you got on. How did it go for you when you went

on? RALPH...

It was great. And it was strange really because it's twenty years since I first

appeared there. 1969 and suddenly 1989 you wonder where all the years have gone,

you know. And it was special for old Ken you know the bloke who ran it because

Ken started it and it was a 25 year anniversary. A lot of people have gone down

the line since then you know. The funny thing is you start off thinking, you

know, oh this is a nice part of my life being

involved in music and suddenly you realise that you're in the sort of the

older generation of musicians now, and that you weren't playing at it, it

is a life... BILLY...

That's right and it's festivals do that to me. You know if you haven't seen guys

for maybe seven or eight years, ten years, twelve, fifteen years you think it's

like last August and so they walk up the path and the guys got grey hair. You

think my God I must be that age too ... ..... But I found the scene difficult to

do you find the folk music scene RALPH...

I used to feel I must be honest I used to feel an outsider and sort of.. I

needed it, but

I didn't ever feel really a part of it.... BILLY...

You see when I played in the folk scene in the various little bands and stuff we

would do the same circuit as you so I didn't meet you for a long, long time

because we were both working the same place you'd be there the previous

Wednesday or Clive Palmer, Bert Jansch, and you all became my heroes and we all

did the same circuit but it's that lovely thing you never meet your heroes

because you're all doing the same...... but you were doing that ...

as a matter of fact you were to blame you and the rest of them were to

blame for the split in the traditionals to one side and the contemporary the

writers at the other and formed two separate circuits... RALPH...

Yeah that's right, that's exactly what happened and as.. I really never felt

part of

the actual folk thing but over the years I suppose because of festivals and

you're growing old with these people we're all growing up and part of it

or am part of it or whatever and when that split came it sort of did two things

didn't it the traddies got very very traddy and very protective and then.

this sort of music was absorbed into pop music I think you know and people put a

pick-up on the guitar and then the next thing it would be a telecaster and so

on. But now it's kind of come round to ... the younger people now hear

older people playing acoustic instruments and it's much more healthy now

I think it's that demarkation has kind of gone and you have a rock and

roll band you have me writing with my songs, you have Martin Carthy with

his songs... BILLY.,.

Yeah, I remember being with you at a lunch in Wembley the sports stadium and I

had to go up and speak. It was one of those Jimmy Tarbuck sports... lunches...

yeah and Lonnie Donegan was in the audience and we were both whispering. And you

were saying, if it wasn't for him you wouldn't be playing and I was the same...

and that was the way I slid into it but when I got in I loved the traditional

stuff I didn't want to do it... RALPH...

No I didn't want to do it either . . but I acknowledged that BILLY...

The people seem to be steeped in --:.--a.£-.a. an aw-ful lot of them. but the

performers aren't they're moving merrily forward it's all becoming part

of something else and... RALPH...

It's very true I think you know even when we were young people were saying we

were nostalgic about something or other I mean the whole music itself is a bit

nostalgic when

you think of Woody Guthrie and what we were trying... I know what image I had in

my mind when I started writing I mean the songs didn't turn out like

Woody Guthrie songs or anything like that or... one or two perhaps... but

I had a very much a romantic image that was attached to this guitar and this

sound the way this instrument went the way it gives the sounds... BILLY...

Hank Williams it was for me or Luke The Drifter which was just the same as Hobos

or... RALPH...

That's right yeah, I had that image in my mind very clearly and I knew what sort

of sound. Cos it wasn't... I don't think it was the song.. I mean after

obviously after Lonnie Donegan there was I think it was probably Jack Elliot the

guy that copied Woody Guthrie the first time, there was the sound of an acoustic

guitar that I had never heard before and I just knew I wanted a guitar

that sounded like that and it went from there well I found the guitar

and... I think BILLY...

What made you write in the first place. RALPH...

I had this tune... and I was in Paris and a friend of mine a guy whose a

wonderful guitarist said that's a really pretty tune you should write some words

to it. And that

was it. And I'd just met Nanna so I called it NANNA'S SONG and it went on the

first album. And then I found that you know you doodle around and you

find that you find things you think oh... I haven't heard that before and

then they would all fit together till there was a tune and then I'd be

obliged to write some words to it... I was never quite confident in my instrumental

ability. And then people... I'd slip them in amongst the Guthrie songs and so on

and people would say what was that one you know... and well actually I said

something I wrote, I never used to give it the title or anything and just

introduce it slowly and gradually the ratio switched till there was more

of my own than anybody elses. But I very rarely, I mean I don't know if

you're the same cos I you know you write as well I mean I never really, I

don't normally think I must write a song about happiness or sadness or about...

I just start writing and I get a line and sometimes its the very last

line of the song. I mean that's actually happened I've written the last line of

the song and gone backwards cos it sounded right. Or... like in NAOMI the one I

wrote on the piano it was: "THE PLACE IS KIND OF QUIET NOW THE KIDS HAVE

ALL LEFT HOME" ... And that was the first line which is in the last verse

and it sort of gave me a plan to move back so I don't often have a clear idea

what I want to write. BILLY...

I've always liked STREETS OF LONDON. Streets of London is part of me you know as

it is part of the great British public and stuff. I don't know if you saw it.

There was a programme on TV where they had sort of mentally kind of slow kids,

they did a concert and the guy came out with a voice... and sang STREETS OF

LONDON with a bow tie... RALPH...

I heard about that yeah BILLY...

He was all nervous and the woman's combing his hair saying right are you ready

John... the hair on my arms... you would have loved it... it was such a part...

you see I don't regard that as one of your songs anymore, you know, it's such a

monster of a song ... How do you

feel about singing it today, does it still have the... RALPH...

Well, you know, its like, it's the song that you can always rely on in the sense

that it doesn't seem like my song. First of all it's so long ago when I wrote it

and it is known and a lot of people know it besides myself. It's still possible

to get back into the sentiment that was there when I wrote it. And also

in today, right, when the situation is, it's probably worse than the

situation described 20 years ago because there's an air of, there's sort of a

cynical attitude, well what can we do on... you know we've got little towns

for crying out loud made of cardboard in the middle of our capital city.

I mean and I suppose people are brutalised by the fact that they are

unable to do anything about it but it gives me a reason to sing it and I've

been... I've pointed out now before I do the song that the situation is even

worse than it was when I wrote it. And that gives the song a currency

which it shouldn't really have it should have all been sorted out by now

but that's the way things are... it's got it's own career hasn't it? BILLY...

I was always jealous of you. I always wanted to be the writer you know like you

and Roy Harper. I wanted to be windswept and interesting.. write about lost love

you know. I was always writing about chicken pie and playing dulcimer dressed in

corduroy, I would sit down with my pipe and corduroys you know. It's really

weird that isn't it. The way that... you know like you try to be something but

what you're bound to be just drags you through it you know. If you try to write

I love you and you love me I'll eventually sing about corduroy and egg cups or

something because I'm not supposed to be singing about love it's not my function

I don't think that's why I'm here. RALPH...

I'm just wondering when after I realised I wasn't going to be Woody Guthrie or

Bob Dylan, I realised that that was no longer on the cards for

me. BILLY...

We had all been locked into this kind of corduroy sort of stuff, that folky

thing, you know a pint with a

handle on it and corduroys. And these guys would press it against themselves and

sing up... and they would go on the stage and throw the microphone away "we

won't be needing this !oooooh!"

Deafened by this drunken natter. You know it was great to hear people... RALPH...

But talking about microphones I think that was another attraction for the

cousins it was the only place that had a microphone. Oh they've got a microphone

down there, so all the soft voiced singers like myself used to be great. It was

only plugged into Andy's hi-fi thing. But it was like, you could sing really

softly into the microphone, wonderful. BILLY...

There was a club in Salford W... the Two Brewers, and it had a microphone

hanging down like the Lonnie Donegnn 12-inch album you know that one where he's

singing up into the ceiling.. I thought I'd get a gig just to sing into this

microphone... good evening ladies and gentlemen that'll do me, I've done it, I'm

on my way home, it was brilliant... I loved it... there was something

spectacular about that. And a lot of good people came through there and

everybody I liked made it, Martin Carthy, everybody all the good guys filtered

through. And for me philosophically it was a great lesson you could see the

good... some of the

duff guys you know shot through and then disappeared, but the good guys just

kept trundling on... ... I've known you for such a long time now, and I have

lots of memories of you, we've spent so many, many times together but my most

outstanding, it can't be a memory I wasn't there, but you once told me - we both

played the Highcliffe Hotel in Sheffield, but I remember you once telling me

that you had a mini and it was snowing and you drove home to London with no

windscreen wipers, and that has etched itself, I don't know whether you told me

this or not, but I've got this thing of you in the mini with your guitar on the

back seat working the windscreen wiper with your hand. Is that what you told me? RALPH...

That's right. I mean when I think of some of the things, well we all did it I

mean it was the sleeping bag in the back - it was a GPO mini van with a sleeping

bag in the back for emergencies you know in case you broke down somewhere. And I

used to rattle up to Sheffield for a tenner. And I said to Win, Win I

can't keep coming up here for a tenner you know - he said I'll give you twenty,

straight away you know. And then I found out he'd been giving everyone else

twenty anyway so that was another lesson of course. But that journey back

obviously I can remember it because you kind of get stoned just looking at these

like tennis balls hitting the window after a while you know. And I fixed up an

elastic band in fact on the wiper because it had gone. So it was an elastic band

on this side tied round the window and a bit of string on this side and I was

driving along like this pulling this piece of string. I got home. BILLY...

I could never hope to play guitar like you or Martin but I could draw another

three people in the lounge. And I enjoyed those days immensely.. .They were

amazingly formative cos you were learning songwriting and singing, and I was

learning comedy and I thought I was going to be a blue grass banjo player but

that was a myth, a dream. I was - because if I had to or not I was going to be a

comedian ... BILLY...

I've been deeply envious of the depth of your voice for many years... RALPH...

That's down to Old Holborn I think. BILLY...

I like the diversity, from you ... the sheer diversity, not only of the lyrics

but the diversity of your melodic capacity. Your ability to change from ragtime

to love song to something about the hiring fair that's the gig for me, I love

it... How do you feel about performance now, live performance. RALPH...

I think it's fair to say that I enjoy it more than I ever did. BILLY...

Well, I am delighted to hear that Ralphie, because it used to be quite agonizing

for you. I used to feel sorry for you... RALPH...

It's still agonising. I mean the cold sweat pouring off the palms of the hands. BILLY...

There's a position I've seen you in with you hands clasped and behind your neck

walking like this before you go on stage - Oh, God. You get ill. RALPH...

I know, I know. It's never been any different but the joy that I get from being

up on stage it's something to do with getting older as well. I just say I'm a

man I'm 43 or 44, I'm 44, you've invited me to come and play at this place,

you've all turned up, you must want to hear, these are my songs and there's...

when things are working out and the sound is right and all the rest of it

I love it and I don't care how many - I mean from the days at the Albert Hall to

playing 300 seaters, it's just the same and I get that tremendous buzz when I

come off the stage and you've done a good job and you've left people feeling a

little better than when they came in. That's great. BILLY...

But how do you find your actual performance changing are you... do you play

more, with more complexity or less, do you like to sing more or play less or has

it changed at all. RALPH...I

think I'm like I'm enjoying singing more now I think that I listen to the little

voice that squeaked out of the Transatlantic records you know and now where it's

become, and I've learnt to do that better, and I think I'm playing better, but

yeah, I do, when I say I seek to be understood But I try to make it interesting

and not just talk about the bare bones of the emotion. But you've got to slowly

find your way into it... Ah that's what he meant, but I do want to be

understood. BILLY...

Apart from the windscreen wipers on the way back from Sheffield there's another

great image I have from you, is from one of your songs when Mr. Connaughton's

motor bike when he kicks it and it starts. I want to jump out of my seat into

the other chair... RALPH...

Well that's exactly what it was like for me you know. I wanted to write a song

about the essential thing of having a dad. I didn't have a dad. And I used to be

one of those kids

who tagged along behind other people's dads you know. Watching them mending

punctures and fixing things, and this Irish fellow Mr. Connaughton lived

upstairs to us, bought this motor bike so every night he'd be there you

know, and everybody laughed it'll never go, you know, that'll never go.

Fe fuhph etc... more adjustment and I'd be in my room willing this thing to go.

And one night it actually.. .you know gigantic explosion and it went. And

he was a lovely guy and it was, well it was back to what we were saying it's

like finding another way to say the same thing. You want to write a song

about not having a dad, what it means, and here's a song which looks like

it's about the man who lives upstairs, but it's actually about not having a dad

in its way. And I was really pleased with that one. BILLY...

Why have you written so much Irish stuff, or have you written a lot or. RALPH...

Well I have a real affection for Ireland and it probably starts with Mr.

Connaughton I mean that's a male voice that was very friendly towards me and my

brother. I was intrigued by him, he was a happy man, he smiled a lot and all the

things that are mentioned in the song. And when I worked on buildings I worked

with Irish lads and I enjoyed their humour, and I loved their... there's some

sort of bravado you know, and joy about, almost recklessness. BILLY...

There's a thing about exiles too that is dynamic really, they exude, even when

they're being funny it's a very... it's a nervous funny it's a loud raucous kind

of funny that I really... what's that, you wrote the most sensational song about

the guy going to the station

with his sister. RALPH...

Oh The Setting yeah BILLY...There

are two magical moments in my career, and one was when you and I were playing in

Belfast and I had just seen the Liberal Party Conference when an Indian man

got up and he spoke about the unemployment. And he said the most poetic

thing that a man without work is a stranger to the seasons. And I told you about

it, I was so moved by this guy saying this extraordinary philosophical thing at

a political party conference and you went away and you wrote a song and I've

never really told anybody before you know that you did it. Because you happily

tell people yourself. BILLY...

I always think of Australia when you I hear it ... somebody saw you doing it in

Perth and told me. BILLY...

How do you feel now about the song ENGLAND cos I saw you singing it in Glasgow

and it went down a storm. I thought this should be very interesting. Cos it's a

love song isn't it? RALPH.

..It is. But you did me a tremendous favour... I mean, remember you phoned me

from Fife or something at three o'clock one morning having heard the demo. Break BILLY...

So what inspired you to write that a love song about a country. RALPH...

I think again it goes back to Ireland, a friend of mine said, I said it's

amazing how when the Irish songs acknowledge the beauty of their country, the

physical beauty, he said to me in Ireland there's a song about every gap in the

hedge you know. And I thought you know that's not reflected in English songs

we've got things like 'Land of Hope and Glory' and we've got you know the 'Rule

Britannia' and 'Did Those Feet in Ancient Times', which is rather a nice sort of

mystical thing. But I wanted, I didn't think there was a song that could be sung

by anyone, whatever their race if you like or their ethnic background that's

born in this country that thinks like I do that it's a very lovely country, it's

a nice place to live, I mean it could be better, God knows but actually when you

go out to the countryside and look at it it's very beautiful and you must surely

have some feelings for it. So that was the brief I had to write a song that

could be sung by a little Indian child, Asian child, black child, or black

person or whatever and then I thought this is going to be hard because all our

songs are about beating somebody else up to prove how much we love the place we

live in, you know. So I set about using the image of the echo of the green hills

running through the city streets and that England is a multi-racial place and it

slowly emerged. And the breakthrough came with the B-flat chord I think it is

and I remember playing it to John Renboume and he said oh that seems to work.

But it was actually that phone call from you up in Fife that made me sure about

it because we're not very good at singing our own praises the English actually,

when it actually comes down to it sort of talking about our... I mean I'm sure a

lot of people find us very arrogant but talking about our country in the same

way that people in Scotland and Ireland and Wales especially are quite unabashed

about it... BILLY...

I think a lot of the time the Irish and the Scots and the Welsh have sung about

it themselves

whereas the English have left it to professionals who always wanted to march,

you know

and even with the Lincolnshire Poacher there's a druddd... dddudduddudd doo.

It's all riddley

turn ti turn ti... music teacher kind of songs. RALPH...

Yeah, well in fact you've just hit on something else - when - because that year

it was

released there was a Royal Wedding and some people actually thought I might have

written it for them I'm sorry Charles and Di I didn't. And then, somebody

else said the Falklands War occurred as well I mean, - and a major record

label that shall be nameless wanted to take it and reset it to capture

the kind of jingoistic feeling that was running -I said that's the absolute

antithesis of what this song is about. We did agree to that. Another record

company released it but only after the thing was over and the soldiers had come

home because I - no one wants to make money out of that kind of- that's

the worse kind of thing. But anyway the song is there it nearly made it.

some people think it was a hit that'll do. It was nearly a hit. BILLY.

..It made it as far as I was concerned I don't care about hits... STRANGER

TO THE SEASON A

man without a job Is

a stranger to the season The

April rain will soak you Like

the worst November brings And

we're tired of the excuses And

the carefully worded reasons Without

Summer there's no Winter Without

Autumn there's no Spring When

the factories close down The

life bleeds from the town Some

politicians tell us build another home But

weren 't they voted into lead us No

one said they had to feed us If

they 'd get us back our jobs Then

we can take care of our own Chorus A

man without a job Is

a. stranger to the season No

music to the cycle Of

the changes will he hear Like

a band without a drummer There's

no Winter Spring or Summer There's

no rythmn to the passing of the Months

that make the year Everyone

is poorer for the millions Concert

Programme JT: You're celebrating your 25th Anniversary this year; of course, but do

you have some idea about what you want to do in the future? RMcT: No, in a nutshell, I just want to keep ongoing, because I think I'm probably enjoying it more than ever before, strange as that may sound, I'm playing better, I feel confident as a man about what I'm doing and what I've done. I keep trying with the idea of maybe adding a few musicians, but I know the problems that will involve, so I'm just perhaps looking at special projects now and again to break-up the solo touring thing. I've now actually got a road band together in terms of having a sound man, a tour manager and a driver and a nice big old bus that I travel around in, and I'm very comfortable and enjoying it very much. I don't want to stop working, that's all at the moment. The biggest new market for me would appear to be Germany, which is near enough to take a bus, but at the moment, the company I'm with over there are so efficient and they provide us with everything. For the UK, we constructed a PA and that's been great. Johnny Jones, who everyone knows from the festivals and so on, tour manages and does the lights for me and sells the records we have, and I've got a great driver called Phil Arnold, who's got his PSV - we're a proper little team. The office provides the posters and publicity in advance and on the night what I like to say is we walk into the theatre, say 'Hello, this is the McTelI tour; we're just going to borrow your theatre for the night'. We dress it, we light it, Doon puts the sound in, we do the show and we give it back to them in one piece at the end of it. So we can actually do that now with a great deal of confidence, and it's been terrific. The biggest crew I had was 20 people, I think, when we did the tour immediately after the 'Streets Of London' single, which was not because we'd had a hit with that record but because I'd planned to go on the road with a band anyway, and that was how many people we needed to do it. That was a mixture of things, and I wouldn't say it was an unqualified success. But this is working out ever so well. We're going to take our own lights, but at the moment Johnny, who has a lot of experience from the Wimbledon Theatre and various other places, goes in and looks at the desk and plugs the lighting for the set. JT: Do you

ever regret leaving the folk club circuit other than financially, which I'm sure

you're pleased about? RMcT: I've got mixed feelings about that, because, as I expect quite a few readers will remember; I was never a very confident performer and it was very fast from first playing in a folk club to going to the college circuit, and I didn't really get the chance to know the circuit like many others. I suppose it was because on my second album I had that song, and that coincided with people's awareness of acoustic music, so I walked into a circuit already able to play a little bit and with a couple of strong songs. When I look back, I do feel a great affection for those days, but I wouldn't honestly have wanted to stay on the circuit any longer than I did, because I always found it incredibly nerve-wracking to be two feet from the first person in the audience. There's another thing about clubs, which I've probably said before - because they were places where people came every week, there was a sort of camaraderie and confidence in the audience which you had to win over, and I was never able to tell a joke in my life. I was famous for my mumblelogues, as somebody christened them once when I tried to explain what a song was about, so I found it difficult and I hated having to break-up the set into two segments; I'd just feel I'd got somewhere and started to roll and then there was another 10 minutes or 50 of anxious shaking before you could get on and do your next bit. But I do have affection for those days and a lot of the wonderful people that took a chance on me when I was really just a kid, and thankfully still come along to gigs - I'm thinking particularly of people up in Chester at the Cross Foxes folk club, and Wyn White in Sheffield, who got me round the North of England and the Manchester Sports Guild, which was a great place, and the Jackard in Norwich, which was run by two guys called Tony. It was nice, but it lasted just about the right time for me - it sounds strange, but as soon as I walked on to a bigger stage, I just felt so much more comfortable. JT: Your

music is a mixture of blues things on one hand, and on the other the almost MoR

type things, with very nice tunes. Do you ever feel that you can read an

audience and say 'I'll just have to play the MoR stuff tonight, it would be

wrong to do a blues'? RMcT: I know when I look around the audience, even today there's a lot of people who know about me because perhaps they remember the hit or perhaps more likely that one of their kids learnt to play the guitar using 'Streets Of London' as a piece and it's gone into their consciousness. They come along still out of curiosity - I still have a hard core at every gig who know every damned thing I've ever done, but there's still these few that I think 'What are they going to make of Blind Willie McTell?'. If they like my music, they're going to have to like his music, at least two or three numbers because anyone can stand that, and I think it's interesting because they can see that it's not that big a jump between the way I play the guitar on 'Hands Of Joseph' and a Joseph Spence tune, or lately 'Summer Girls' and a slow blues by Blind Arthur Blake. I think there's a space for them, and I do know that as a result of being that kind of mixed-up, that a lot of my audience have turned onto these old guys - not a significant number, but quite a few have. I'm afraid that although the overall sound of my albums is for want of a better word AoR or MoR or whatever; it's still challenging if you listen to the subject matter. We did a compilation album of love songs for Castle Communications, but they're not just about 'I love you baby', they touch on adult aspects of love and life, and quite frankly, on every album there's one track that makes you go 'Oh', or there should be - using a nice melody is a subversive way of getting someone into the subject matter and facing something that perhaps anybody else might have taken full on with a full thrashing rocking backdrop. If I wanted to write about repatriation or racism, to do it to a light hearted sounding thing like 'Harry Don't Go' is much better than to rant and rave about it, and I've always done that, but not everybody will understand. For example, 'Naomi', which is a very honest song, has resulted in lots of people naming their little girls Naomi. Equally, a lot of people think it's too tough to say those things and be that honest, and they shrink back from them. JT: Until comparatively recently, your blues fans must have given upon you

ever playing the blues again on record ... RMcT: It's partly that over the years of playing solo. you are pretty exposed up there with the voice and one guitar, and one of the things that kept coming back to me was people saying they didn't know I could play the guitar like that or whatever - in between the last studio album, 'Bridge Of Sighs', and the current one, I thought why shouldn't I do a blues album, and it's very easy to detect from what I've chosen to record on the last two albums what my record collection contains. I'm sure we all had them in the Sixties, but nevertheless, it's been a great success and a lot of people have been pleasantly surprised by the guitar playing, I've got a few more fans for it and I've even managed to get on programmes that I would never have ever been played on, and so it's been a great thing, and now I get a few requests every gig for a blues or a rag, which is nice. JT: Do you have a preference? RMcT: If I had had a voice like Dave Kelly and been able to play the guitar like I do, I would have probably stuck with the blues thing, but I always felt my voice was too smooth, too white, too warm, to do the songs that I love and that I play at home for my own pleasure, so I might well have taken a different route if my voice had sounded differently, and I think I would have written, but in a different way. I was listening to Bono on a TV concert, and he's got one of the few voices that sounds like a young Luke Kelly in places and like a real raucous rock singer in others, and he's got the perfect voice to do that kind of thing. He's a very lucky man, and he gives credibility to both sides of the coin, but when somebody like me tries to - I'm a bass/baritone if anything, and I can't sing up in a register with Robert Johnson, and if l sing it low, it doesn't sound urgent or anxious enough. I think you are bound a little bit by the sound of your voice what you can actually take on with real credibility. JT: The other thing is that you have not written many major protest songs

recently, although probably your most famous one apart from the hit is 'Bentley

& Craig', which you've been playing for how long now? RMcT: I wrote it in about '78 or '79... JT: What do you think about the recent news? RMcT: I'm a Croydon boy, and in 1952 when it all happened, I was very well aware of what was going on. The newspapers were full of it, people were talking about it, I was about 7 or 8, my mother worked in a chemist's shop which Iris Bentley used to frequent as a young girl, and I think my mother knew Derek vaguely. You've got to remember that this was the first policeman who was shot as far as I was concerned and killed in England since about 1910. The war was only over by about five years, there was huge public debate and outrage that a policeman had been killed, and there was also a great fear about something called coobboys, which was a precursor of the teddy boy era, where gangs of kids would mug people at their front doors, and there was genuine fear around at the time. However, even as a young kid I knew that this man hadn't killed anybody, and yet he was hanged. Now you don't get over something like that. because no matter who you talk to, adults couldn't give you a satisfactory answer; so it always was there. I used to live very close to where the murder took place, or the accidental shooting or whatever you want to call it, and every time I walked down that street I used to look at this building and think about that incident. I think in 1974 there was a TV documentary which laid out the facts of the case very clearly, that there were all sorts of doubts and I thought I had to do something, because it had all the elements of a Woody Guthrie ballad - a terrible injustice had occurred, and because the politicians who were alive and at the time did nothing to save this boy's life, from the murder in November, he was dead in January. From the incident to his execution was two months - unbelievable! I wrote the song and I took my cue from the way Woody would have done it - whether or not he used the words 'Let him have it' is debatable, but I did it in the way that it was 'let him have the gun', not 'let him have the bullet', which Woody would have done - he would have left the debate open, I felt. I started playing it, and the more l played it, the more intense I felt about it, the better I played it, because it's quite a tricky guitar part as well. Then I heard that Iris had heard it and loved it, and I started playing it everywhere I went all over the world, and when the film came out - which I haven't had the courage to see yet - I just felt I'm just part of a movement that will one day get this boy a pardon. Iris Bentley's been dreadfully ill most of her life, but has fought relentlessly. I think this case has kept her alive and given her a reason and I met her for the first time at the Croydon Fairfield Hall concert recently. We invited her along, and she was a perfectly wonderful brave lady. I announced the song - I always get a bit emotional about things like that, and I said I wanted to do a song about an incident that took place in Croydon, one of the most infamous events, and I wanted to dedicate it to Iris Bentley for her bravery, and the whole audience gave her a round of applause. So I had to play a little bit longer while I swallowed the lump in my throat before I got into the song. I really gave it the lash that night ... JT: There's your other song about unemployment, which is still very much

in the spotlight. RMcT: I wrote that song because I felt unemployment would be an issue how wrong I was, because many of the unemployed voted for the government that was probably responsible for it. I've made some pretty hefty statements on-stage from time to time. I don't make a habit of it but every now and then, especially with 'Streets Of London' now, 20 years on and still the same situation. It's worse, because the public have become numb to the situation. It's rather like putting up another picture of a starving black child, people just go 'Well what can we do?' and in the end they're brutalised by the experience and fail to be moved. That's why somebody like Geldof and the people who got behind him did such a phenomenal job to shake our consciences about hunger, but it's bad again JT: This

seems to me the absolutely perfect stage for someone like yourself to write a

song or an album of songs about the way that the world in 1992 has suddenly

changed dramatically and yet it's probably worse now than before it all started. RMcT: Honestly, I tried, I sat down with Mick, my manager - we were talking about what a man of my mature years could write about, and he suggested 'From where I stand now', and I thought about it - it would be so depressing! There's got to be light at the end of every tunnel - in every McTell song there's a glimmer at the end. I could never write one with just the bleak view, there's always got to be the triumph of human spirit or endeavour at the end, or ability to pull themselves out of a problem, and right now, I don't know - I'd have to get my thoughts organised, and maybe I'll have a go. JT: You are in an almost unique position - maybe you and Tom Paxton, but

maybe he's a little bit old to be doing this, You still have your health and

strength and you're not old, and I think that you could actually stem doing this

because you have a large following who would listen: it's not only the young

lot, who are disenchanted with the music they're being peddled because it

doesn't mean anything - the 28th remix and that kind of rubbish - whereas you

could give them something that's got some quality and also some content. RMcT: I feel I should, and I must say I've enjoyed the harder-edged things I've been working on simply because I know now that I'm outgoing to be the English Bob Dylan and I have established a place for myself within the general sphere of popular music. I don't see compromising - even in a song like 'From Clare To Here' there are areas of controversy. I don't want to change the way I feel in order to get more overground. Of course TV is the way through, probably more than radio for me right now, because I think kids respond and music has become a fashion accessory more than it ever was - sure, the mods had their music and the rockers had theirs, but I feel music now, especially as it's allied to dance in particular and to certain types of playing, is more and more a fashion accessory, and music is tailored for the market more than it ever was because people in the music business understand that it is a market and that it can be manipulated. JT: What's

happened to music is tragic - it just seems to have reached the end of its

usefulness, rock 'n' roll that is. RMcT: It will be the same as we always said in the folk scene - the question you haven't asked, and I'm really not qualified to say: with regard to the revitalisation of the folk scene. it won't happen with just young Kathryn Tickell, who plays beautifully and is so attractive and does a great show, it's going to have to be spotty 'erberts of 18 picking up their guitars and strumming acoustic songs and writing again. What's happening in Ireland is very interesting, because I think that has happened there to a certain extent, largely because it was never out of favour anyway - you'll always hear a bit of diddly diddly alongside whatever else is in the charts, so the kids grow up with the two cultures in parallel. I saw a clip of the Saw Doctors the other night, and I thought they were great - full of life and vigour and writing about things they cared and were concerned about, largely acoustic, but until the youngsters start doing it, it won't be revitalised, and it's the same with rock 'n' roll - everybody thinks they've got to have a sampler and a synth and a drum machine and stuff on tape - I'll tell you what, I wish there were some live tapes of Cyril Davies at Eel Pie Island when I used to go. By today's standards of sound quality and everything, it probably sounded dreadful, but it swung like the clappers. You could dance to it if you wanted to, or listen to it and go home and try to play Geoff Bradford guitar riffs to see if so could retain any of them - that's what's needed, I feel, to get back to the organic approach to music. JT: I think

we were fortunate to have grown up at a time when the Stones and the Yardbirds

and Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner and Manfred Mann were all unknowns and were

very available any day of the week. RMcT: I remember somebody at Eel Pie Island saying: '2/6? Who is it?', and the bloke on the gate saying 'The Peter Butterworth Blues Band', because it had gone up to three bob from half a crown for Paul Butterfield. JT: To go to a gig today for anyone you've heard of costs £6, and people

on the dole can't afford it. RMcT: That's true, I know, but I still think we get our music cheap: touring is so expensive and I'm talking about the older bands who've gone out of favour but still put out great music, like the Steve Gibbons Band, Jackie McAuley and Ron Kavana, people who put down great rocking music for a fiver, which is the price of a couple of pints these days. I still think we're very fortunate that way. JT: Today's

teenagers don't regard music as very important like we did - in our day, there

wasn't much else to do, because we didn't much want to watch TV because there

was nothing on. RMcT: Again, last night I was thinking how great it would be if there was music on television when I was a kid, and now there is music on TV, and there are diversions, so perhaps kids aren't going out so much and making music. I don't want to become the old soldier, but when I got into the music thing, trad had been and gone and these guys were going "Listen to that - three chords is all they know. They wouldn't know a blues in B flat without a bloody caps and all that", so there's some truth in it, I suppose, even for them - each generation probably thinks they had the best of it. I certainly think our generation had the very best of it, because I'm still going back, actually, to jazz music which I'm very fond of and stuff from the 1930s upwards right through to the Fifties and still finding great music, so l don't feel deprived. We also came in at the beginning of rock 'n' roll, and then the blues revival and so on. I sort of got off somewhere. In the mid-'70s, I think, when it all got a bit pompous and silly, and the punk thing, I could see why it was there, but - I suppose in one way it led to a kind of cleansing process occurring. JT: There have been so many covers of 'Streets', from the Anti-Nowhere

League on. How do you feel about them, and which would you choose as your

favourite:? RMcT: There's been about 167 or 8, I think another one was done the other week, and I don't know which ones I'd pick. I would probably definitely pick Mary Hopkin, because she did it absolutely straight ahead, almost immediately the song came out, and I played guitar on that track, Mary did it beautifully. And I think Glen Campbell, because I admire the man, he's a great guitar player - he's lost his ways bit, which I think he'd admit. Harry Belafonte did a great version where he changed the tempo and some of the words, Cleo Laine did a lovely version as well, but the one I want to hear is Bruce Springsteen - apparently he played it onstage after he came back from London, although he hasn't recorded it, and somebody from New Zealand's promised me a pirate tape from the audience. The other one was Aretha Franklin sang a bit of it when she was in London onstage, as part of a medley of songs about London which I would like to have heard. It might be interesting to compile an album, because the diversity of people who have recorded it almost puts it in the same league as 'My Way'. At least Sid Vicious didn't do it' but I think he might have got around to it. The Anti-Nowhere League came to a gig of mine, sat in the front row all sprawled out - it was obviously a publicity stunt, but It's amazing - I've actually had kids coming to my gigs who've heard the song for the first time by the Anti-Nowhere League, and didn't know it before. JT: Did you

select the tracks for your silver anniversary album? RMcT: I'll tell you the story. I had a hit in Germany with 'Streets'

again, at the same time as it was a hit here, but in the German charts, there

were three versions of me singing it, all different, all in the chart at the

same time, which has to be some sort of record. One I did for Transatlantic I

did in 1969, then there was the hit version, of course, and one I did for a

company called Paramount that disappeared - they recorded me and Melanie. There

was also a German language version. Recently, I've got a German agency who

believe in me very strongly, it would seem, and want me to work more in Germany.

It's a wonderful place to work as far as an artist's concerned because they look

after you, they've got nice halls to play in, they look after all the details.

They wanted an album, so l thought as it was 25 years, let's give them some

songs that go back almost right across the board, but have some cohesion, so

they drew up a list of things that they would like, and Mick and I decided to

keep the body of what they wanted and see how best we could complement it with

our choices. So it's a bit of a team effort, and I'm glad of that really - if

I'd just picked all my favourites, it might not have been the album that they

need. When we said we were doing it, we got interest over here with Castle

Communications, who've got some of my old catalogue anyway. Which is why Castle

Communications came in because they do seem interested in my back catalogue. I

would be happy to get as much of it out with one label as I possibly could. It's

incredible to me that weedy as my voice sounds on some of those early

recordings, and as hesitant as I sound, the songs still go in, and when I get

requests before I do a show, I get anything from half a dozen to a dozen

requests from the audience - there's as many requests for those early songs as

for the newer material. People just picked up on it quite recently, the very

early stuff, and that's very strange to me. What I'm trying to say is that

despite the presentation, the song comes through, which is very heartening to

me, so l would like to see more of my back catalogue out. At one point, I used

to think that they sounded terrible, I was singing out of tune and I made a

mistake halfway through on the guitar ... there was one recording that was

straight to stereo or straight to 4 track, and I didn't want it out. I've been

through all that and as far as I'm concerned, I'd like it all out, I'd like it

all available, because I'm not ashamed of anything I've ever written. Concert

Programme JT: Let's get on to Dylan Thomas. Has he been someone who has interested

you most of your life? RMcT: I had a very short education. I left school at 15 and I was a confused kid - very confused - and there were plenty of us about. I joined the Army for a dreadful six months like Roy Harper and, funnily enough, Billy Bragg, and got out as soon as I could and went back to school, but I'd just discovered girls and music and everything and I can't say my education was very complete. When I drifted into music, somebody introduced me to Dylan Thomas, a name I knew, and I read the poems with delight and especially the short stories and little snippets he wrote - I loved them. There was a lovely thing about the language. That would be the early '60s, and then nothing until about three years ago. I was at a friend's house and we'd been to dinner, and as I was leaving, there was this biography by Constantine Fitzgibbon lying on the table as we went out of the door, and I said it looked interesting, so she said I could borrow it. I did and read it and dropped it in the bath, went out and bought a replacement because I just saw the cover and hadn't checked the author; and they'd used the same picture on another book by Paul Ferris. So I now had two, and I read that as well, and he became important to me immediately I'd read the first book because first of all, I was now older than he was when he died and my opinion of his life - I would never presume to judge his work because I still don't understand a lot of the things he wrote about - but in his life, I could see so many things, especially in America, that have happened to me and to people I know, especially those solo artists, including myself, 'who had a propensity for drink, never to screw up onstage, but to comfort themselves or provide confidence either before or after a gig, and the problems that leads to. All these human failings endeared him to me so much, and put next to his art, which is considerable, I developed a real kind of empathy for this character who was almost totally hopeless as a human being, absolutely hopeless, a walking mess. Another book I got was one by Daniel Farson called 'Soho In The '80s', and there's just one mention of Dylan Thomas in it at the end: 'I only met Dylan Thomas once and it was at some bar. He was just leaving for America, and he noticed that the magazine I was carrying had a short novelette by Raymond Chandler in it'. Dylan's main source of reading was pulp detective fiction, in fact Caitlin says in one of her books that she had to actually hide these trashy novels so that he would get on with his work in the shed, and suddenly I got an idea: I wanted to write about Dylan, but not as some sort of authoritative literary figure. so why don't I adopt the persona of a gumshoe, almost like an alter ego, a Jimmy Cricket or a conscience: a figure who is sort of slightly involved, but trying desperately to be impartial, warming to his subject the longer that he observes. He's always there at Dylan's shoulder, jotting down his notes and thoughts about the way this man's life is going, because that's how I got involved - I became a detective, wrote it all down and refined it six times until I'd got it into shape, and then I read it to a friend who was so supportive and said he didn't know I could do something like that - I didn't know either. It's almost a poem, it rhymes here and there and it's got certain rhythms and so on, and that was going to be the end of it, but I got an idea for a song to go in a position within the story, and I felt that if I got five songs and this story, I could probably have an album. In fact, I ended up with nine songs and two poems read by Nerys Hughes and Bob Kingdom in the voice of Dylan Thomas. I kept thinking of all the things that had led to him: a Welsh schoolmaster once said to me in 1967 "I like you, dear boy - It's better to be a big frog in a small pond" and I kept thinking about Dylan in little parochial South Wales. He had to break out of the pond and go to London, and then he had to break out of London and cross the big pond to America, so this image of water was tied up in it. This isn't a boating lake, this is an estuary that leads out to the sea which is the way the cycle closes, and I just got so fired up about it. JT: I gather

that it was Maggie Reilly who did the female vocal - I thought that was a

coverable song. It's obviously not going to be a pop record. RMcT: That's right, it's probably the least commercial thing I've done in my life, but I had to do it - I was driven, for the first time in my life, really driven, to see something right through to the end, and confident that it was good and grown up work - usually, people say 'Oh no, not another concept album', because so few of them really work, but because I'd tried to take this different view, a non-academic view, and just look at a life, a life going wrong, a life running out of control ... We had the benefit of hindsight and all these books about him to put the picture together, and I'd like to think it's a kind of contribution, not just to the mythology, but to understanding the man from a sympathetic view. JT: I think the prose is very impressive and maybe you should do more ... RMcT: I'd like to try - if I get fired up again I really will. JT: Was this commissioned by the BBC? RMcT: Not at first. I just did it with Martin Alcock - I told him I was doing something I felt very strongly about, and could he help me. He was down the next day, and he's one of these guys who doesn't have to look, he just writes out the charts and asks what the next one is. We went through eight of the songs, I think, which were done by then, and we talked loosely about what he could do with his machines, went into the studio and did eight songs and mixed them in two days, and they have formed the basis of everything on my album, my version, except for the Maggie Reilly song, as that hadn't been written. Mick met Frances Line, who's the Head of BBC Radio 2, in the street, and she commissioned it, Graham Preskett did all the arrangements, and poor Michael Elphick, who's got the perfect voice to do the detective's part, had to read to an orchestra with no sound separation, so there was no chance of patching it or anything, but I wanted to make sure I had my own recorded version to go out. So we re-recorded an album version, but I did the narration. It's a very carefully thought out musical arrangement which I think goes so seamlessly that Graham probably won't get enough credit for it. JT: I think

'I Miss You Most Of All' is ripe for covering, and in fact several of the songs,

like 'Summer Girls'. RMcT: 'The Irish Girl', 'Slipshod Taproom Dance', 'Conundrum Of Time', 'Milk For One' - that's a simple act of kindness which even turned against him, he falls asleep and the milk he was saving for her is put in his cup. It's a segue between the night when they go home rucking and rioting and probably had some drunken screw, and she wakes up in the morning and doesn't even realise he's been to bed, which is supposed to underline their relationship at that point. JT: When I

heard the album the first time, I wondered whether it was about Brendan Behan. RMcT: One of the reasons people drink is to put up this bravado of defence against criticism because they're so vulnerable, and Dylan refused all his life to have analysis done on his poetry and refused to discuss what it meant, he would make up silly excuses rather like Bob Dylan did - I found that quite interesting. Bert Jansch used to say it's about anything that you want it to be, which it clearly wasn't because he always had a clear idea, but would not discuss it. I worked so hard at trying to make sure people did understand what I was saying: I was always prepared to talk about what mine were about, although I don't think many people needed to ask, but there is this thing about Behan and Dylan and quite a few others that I know, like Van Morrison. 'Wonderful Country' is the working title to the one which includes the 'You By My Side Again' line. I was going to call it a proposition of prepositions - 'to wake up at home with you by my side in the house on the shore in Wales'. To get them all in one line I thought was a sort of Dylan thing. 'Get Me A Doctor' is just a veiled reference to a certain doctor in New York, who, despairing of Dylan coming in once again with the DTs, gave him much too heavy a shot of whatever it was which sent him into a coma. It wasn't the drink, and he would have survived without that doctor, it's commonly thought. I stuck 'Roll In My Sweet Baby's Arms' on the end because of that reference earlier on to waking up in each other's arms. I couldn't quite remember where I knew that song from, but it's an old country thing, I think - traditional hopefully. JT: 'I Miss

You Most Of All' is the production number. RMcT: If we'd had the chance, we would have done it again, simply because I got so fired up on some of these songs I wanted to keep the intensity. If anyone wanted it, I'd be prepared to do that with a bigger arrangement and a drum kit and a longer guitar solo by Martin. JT: That one would be a single. The last song - 'Come Down To The Park'? RMcT: That's a reference to Kildonkin Park which was near the end of the street where he grew up, where his imagination took flight and so did mine. Often there's a way that these things refer to me - the park was the place where you exercised your dreams and the things that you'd read about or seen at Saturday morning pictures or whatever. By tying your raincoat round your neck with one button, you became Zorro or Superman, and the trees and the bushes could be anything you wanted them to be. It's also the place where you lose your boyhood, where the boys who've been playing on their own all of a sudden are attracted to the girls and the girlish shrieks and boyish shouts become another thing and the cheeks burning from the chase is the kiss chase. You're becoming a man, other emotions and fantasies are creeping in and at this point you've got to watch this boating lake safety because it's not a boating lake, it's an estuary and you'll be off soon, so be careful, beware. Then to tie the whole thing back to the sea again - what do I do? Do I close it with the finality of Dylan's death? I didn't want to do that, so I've missed the first bit and we've started at school with an imagined deception and we finish up with him becoming a young man, feeling the constraints of home. I think one of the best lines in it is 'Now belongs to be homesick' instead of sick of home and tired of staying here, but this is fraught with danger because this very leaving is moving away from the comparative safety of Swansea, which is eventually going to result in the recognition of his genius but also is the cause of his death. JT: The thing this is possibly most like is 'Lark Rise To Candleford'. RMcT: Which I've never heard, although I'm ashamed to admit it. I read the book and loved it, but I've never heard 'Lark Rise', which was coincidentally co-produced by Mick. JT: Many of these things have little discernible plot, but that couldn't

be said of your story. RMcT: I wanted to call it 'The Fat Boy With A Note' because I thought it was the summation, a sort of a quick character assessment of him, the boy that can wriggle out of something with a little bit of charm and a little bit of subterfuge, because it was to come later on in his work, and this adopting of roles - it could be construed as a bit insulting. The other one was maybe to call it 'The Artist's Life', because he did 'Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Dog' in response to 'Portrait Of The Artist As A Young Man', and most recently I wanted to call it 'The Certain Tide', because that's the name of the poem that Bob Kingdom reads about 'I know there will be a certain tide that will return me to the pond'. There are other artists whose lives have gone along a similar route. JT: Some of the melodies are in that Fairport-type traditional folk style,

like 'The Hiring Fair' thing. RMcT: That one was planned, because I wrote it for Fairport - I was thinking about 'Matty Groves', starting in a minor key and then once you've started in a minor, there are only two options where you go next, which gives it that traddy feel, but I didn't really try for that here. I let the tunes come out however they wanted to. I always seek melodic qualities - it's hard to write a good tune that isn't trite, but I really do try to write melodies that people can sing along with and retain. I'm amazed at some of the things that pass as tunes, from David Bowie onwards, just how many rules you can actually break and people can still join in, because I'm still fairly conventional when it comes to melody writing and tune construction. I don't think any of them hold a candle to the best melody writer of my generation, Paul McCartney, who's incredibly good at melodies, but I do seek to be melodic. JT: I agree that McCartney's gifted, but compared to Cole Porter - RMcT: Now you're talking - there's man who not only had the most uncanny other worldly sense of melody, and I'd put Hoagy Carmichael in that bracket, but Cole Porter also wrote those lyrics, and Hoagy only ever wrote one lyric, and Paul doesn't seem to change much of what he writes lyrically. I'm a great admirer of his tunes, but I overheard a guy in an American bar once saying 'How can you make a whole album without making a single statement?'. I do try to be melodic, and it's usually out of the guitar or the piano, it may be just one chord, and by moving one finger you get another chord that voices it differently, so that the next chord you make wouldn't be the one you'd use if you hadn't moved that finger. I suppose this is how all music is constructed, but sometimes you can take a hack sequence and by just changing one or two notes, it leads you into something else, and both in 'I Miss You Most Of All' and 'Wonderful Country', that happened, because I wrote both of those on the keyboard, and it's always very interesting to write on a keyboard rather than a guitar if you're a guitarist, and probably vice versa. With 'Slipshod Taproom Dance'. it's a real fingerbuster to play because the inversions sound like somebody strumming along on minor chords, but when you listen to what the guitar's doing, which became the theme for the detective, it's very interesting. I bad a lot of fun doing that, getting the songs to come out of the guitar or the piano. JT: I think

it'll be a triumph, but maybe not a commercial triumph - an artistic triumph

without any doubt. The problem is that people like you have to make a living,

and it's art versus commerce. RMcT: People might say that without going for the soft option, I haven't taken many chances in my life artistically. I could dispute that, but I won't bother. I've had a priority above all which is to feed my family and take care of them, and I've been very privileged to have been able to do it with the aid of a Gibson guitar and a rented room, if you like, for the people, but as I said, there comes a time in anyone's life where you wonder what you're going to do next, and this was something I got involved in and if it does divert people from thinking that I wrote 'Streets Of London' and gives me some other credibility, that's fine with me, and I'll take the loss on the chin. JT: I think

it's a new start for you, a new direction, because things are polarising, either

getting better or worse, they're not remaining in the middle, and that's

especially true of music. There's a lot of awful music which is supposedly

popular at the moment. but there is beginning to be an upper echelon of people

like U2, John Mellencamp, Van Morrison, who are experiencing fresh popularity. RMcT: You can detect it certainly with Van, it's like a rebirth for him. JT: You seem to have recovered from what may have been a writer's block